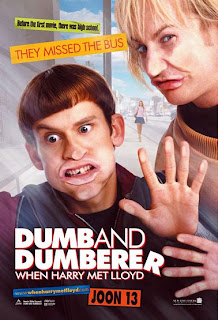

LOS ANGELES - A Los Angeles police officer takes aim at a looter in a market at Alvarado and Beverly Boulevard in Los Angeles on April 30, 1992, during the second night of rioting in the city. VICTORVILLE — Christopher Anderson was living in Baldwin Hills on April 29, 1992 — the day that all hell broke lose in South Central Los Angeles, not far from his neighborhood.

His mother called him earlier that day, concerned about the Rodney King verdict.

“My mom told me and my sisters and brothers to come over and leave work early. She said, ‘I have a vibe something is going to happen if they do not find these cops guilty,’ ” said the Victorville resident.

But the premonition did not prepare Anderson for the devastation he would encounter.

That day, three police officers were acquitted by a predominantly white jury in the beating of motorist Rodney King, while the panel could not agree on one count for the fourth police officer.

What ensued was the worst riot in modern U.S. history, with damage estimated from $800 million to $1 billion. Rioters looted stores, set fires, beat innocent bystanders and shot at police, with 53 people killed in the process.

On the 15-year anniversary of the Los Angeles riots, Anderson mused about the conditions that led to the chaos.

“If (elected officials) don’t sit down and try to get to the roots of the problem, who knows? Maybe we’ll wake up one day and this city will be on fire like that,” he said.

Though the conditions that led to the riots are not exactly duplicated here, the population has grown considerably in the last 15 years, putting ethnic groups in close proximity who have not previously had a presence in the valley.

With gangs from Los Angeles added to the mix, tensions have erupted in the schools between Latinos and blacks. Anderson, whose parents had moved to Los Angeles from Alabama not long after the 1965 Watts riots, found it hard to believe that residents would destroy their own neighborhoods.

“Why are you stealing from your own community? You're hurting yourself,” he said. “Here I am driving down Crenshaw Boulevard and there’s people losing their minds. You go out in the street and there’s the National Guard. It was like a different country, it wasn’t America.”

William Lundelius, a retired chief warrant officer with the United States Army, was called in with the 49th Military Police Brigade to assist when rioting broke out.

“I’m in a quandary as to why it took L.A. so long to ask for the National Guard’s assistance when everything was going to hell in a hand basket,” said the Phelan resident.

“They were doing all the damage on their own home turf,” he said. “Nothing makes sense. I couldn’t understand the rationale behind it. Rioters were taking pot shots at firefighters who were trying to put the fires out.”

Racial tensions in South Central Los Angeles provided fertile ground for the rioting. Between 1980 and 1990, about 22,000 manufacturing jobs in the area were lost, with Firestone, Goodyear and General Motors closing their plants.

Many local businesses were owned by Korean Americans, who had been struggling with harassment from gangs and lived on edge trying to protect their property.

Not long after the Rodney King beating in 1991, a 15-year-old black girl named Latasha Harlins was shot and killed by a Korean-American store owner, Soon Ja Du. Soon Ja had observed the girl putting juice in her backpack, but a court review of the security video revealed that Harlins was planning to pay for her purchase. After a scuffle, Harlins put the money on the counter and fled, only to be shot in the back. When bedlam broke out, Du’s store was burned to the ground.

“What I think took place let off some steam, but I don’t think it solved the group problem,” said Lundelius.

While the four officers in the King case were originally mostly acquitted, two lawmen, Laurence Powell and Stacy Koon, were found guilty in a 1993 civil trial.

The retired Army officer also reviewed the video of the Rodney King beating, noting that King was under the influence of PCP at the time and was resisting arrest.

“I've been in situations like that, and I’ve actually had to deal with people on crack or PCP.”

Lundelius said that when someone is resisting arrest who is impaired, the training is to use your baton on the fleshy parts of the arms and legs to wear down the muscles.

“When it went to the head, that’s when you overstep your bounds,” he said. “You just don’t do that, I don’t care who you are, it’s not right. ... The officers who stepped over the line deserved what they got.”

His mother called him earlier that day, concerned about the Rodney King verdict.

“My mom told me and my sisters and brothers to come over and leave work early. She said, ‘I have a vibe something is going to happen if they do not find these cops guilty,’ ” said the Victorville resident.

But the premonition did not prepare Anderson for the devastation he would encounter.

That day, three police officers were acquitted by a predominantly white jury in the beating of motorist Rodney King, while the panel could not agree on one count for the fourth police officer.

What ensued was the worst riot in modern U.S. history, with damage estimated from $800 million to $1 billion. Rioters looted stores, set fires, beat innocent bystanders and shot at police, with 53 people killed in the process.

On the 15-year anniversary of the Los Angeles riots, Anderson mused about the conditions that led to the chaos.

“If (elected officials) don’t sit down and try to get to the roots of the problem, who knows? Maybe we’ll wake up one day and this city will be on fire like that,” he said.

Though the conditions that led to the riots are not exactly duplicated here, the population has grown considerably in the last 15 years, putting ethnic groups in close proximity who have not previously had a presence in the valley.

With gangs from Los Angeles added to the mix, tensions have erupted in the schools between Latinos and blacks. Anderson, whose parents had moved to Los Angeles from Alabama not long after the 1965 Watts riots, found it hard to believe that residents would destroy their own neighborhoods.

“Why are you stealing from your own community? You're hurting yourself,” he said. “Here I am driving down Crenshaw Boulevard and there’s people losing their minds. You go out in the street and there’s the National Guard. It was like a different country, it wasn’t America.”

William Lundelius, a retired chief warrant officer with the United States Army, was called in with the 49th Military Police Brigade to assist when rioting broke out.

“I’m in a quandary as to why it took L.A. so long to ask for the National Guard’s assistance when everything was going to hell in a hand basket,” said the Phelan resident.

“They were doing all the damage on their own home turf,” he said. “Nothing makes sense. I couldn’t understand the rationale behind it. Rioters were taking pot shots at firefighters who were trying to put the fires out.”

Racial tensions in South Central Los Angeles provided fertile ground for the rioting. Between 1980 and 1990, about 22,000 manufacturing jobs in the area were lost, with Firestone, Goodyear and General Motors closing their plants.

Many local businesses were owned by Korean Americans, who had been struggling with harassment from gangs and lived on edge trying to protect their property.

Not long after the Rodney King beating in 1991, a 15-year-old black girl named Latasha Harlins was shot and killed by a Korean-American store owner, Soon Ja Du. Soon Ja had observed the girl putting juice in her backpack, but a court review of the security video revealed that Harlins was planning to pay for her purchase. After a scuffle, Harlins put the money on the counter and fled, only to be shot in the back. When bedlam broke out, Du’s store was burned to the ground.

“What I think took place let off some steam, but I don’t think it solved the group problem,” said Lundelius.

While the four officers in the King case were originally mostly acquitted, two lawmen, Laurence Powell and Stacy Koon, were found guilty in a 1993 civil trial.

The retired Army officer also reviewed the video of the Rodney King beating, noting that King was under the influence of PCP at the time and was resisting arrest.

“I've been in situations like that, and I’ve actually had to deal with people on crack or PCP.”

Lundelius said that when someone is resisting arrest who is impaired, the training is to use your baton on the fleshy parts of the arms and legs to wear down the muscles.

“When it went to the head, that’s when you overstep your bounds,” he said. “You just don’t do that, I don’t care who you are, it’s not right. ... The officers who stepped over the line deserved what they got.”